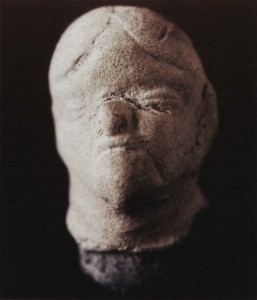

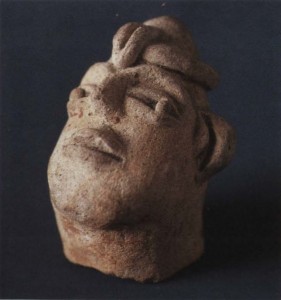

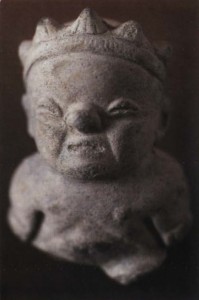

During the documentation process for the preparation of this text “Art and disease”, which accompanies the online exhibition “Coronavirus, fear and courage”, as a curatorial text that accounts for its theoretical framework, the first interesting reference localized in the network was a work by Hugo A. Sotomayor Tribín: “Diseases in Colombian pre-Hispanic art” (1991). The author is a Colombian doctor who operates in the field of paleopathology, adopting the analysis of pre-Columbian ceramics as a method of knowledge; In this sense, what it takes as a means of study are material resources contributed by research carried out in the field of archeology. Hugo A. Sotomayor Tribín has focused his interest, particularly, on the study of knowledge of diseases in the past prior to the conquest of America that began with the arrival of Christopher Columbus. That is, it is ultimately a work of an anthropologist by vocation. In fact, in the presentation of a collective book on this subject, Approaches to paleopathology in Latin America, he did not hesitate to recall what the Colombian Constitution says in this regard about the pre-Columbian experiences and culture, when he recognizes the multi-ethnic and multicultural in the country, which “forces all Colombians to recognize and respect the medicine of indigenous peoples”. This work contains some of the items that have significantly structured the organization of the exhibition, which, as we discussed when presenting it, has had to address what in the end has been seen to constitute the most relevant problem of an online exhibition, which is the to orient themselves in the sea of the Internet, defining the way in which the resources that are in the network are taken, and its reformatting to be returned to it, and all the issues that this brings into play. Those items have been: iconography and symbolism. Because, unlike the works of anthropology and ethnology in use (that is, those from the West, with Claude Lévi-Strauss at the head), in the work of Hugo A. Sotomayor Tribín it is not assumed that they are mystical explanations or magical ones that provide support or serve as a frame of reference to the way in which diseases were approached in the past, but instead seek the information provided by the archaeological remains by analyzing these objects, conceiving them as elements that offer images that are the representation of pathological phenomena, which in turn contain traces of the way in which these pathologies were approached and of the significance attributed to them in the community. In short, we are in the presence of all the factors involved in the creation of symbols, with the iconography at his service.

From this first approximation, a main conclusion emerged ―which has only been confirmed throughout the study with successive new data and contributions―, to which we have referred, and to which has been added the finding of a strong differentiation by gender when approaching the subject, since while men use art to study diseases, women use it as a means of healing or to reflect on the healing processes. Thus, for example, regarding the masculine side, in addition to the case we have referred to earlier, from the studies carried out by Hugo A. Sotomayor Tribín, in view of pre-Columbian archaeological remains, we have the case of the doctor forensic medicine professor Alejandro Font de Mora, who has seen in the following paintings that are part of the history of art, the diseases that are cited, which he reported in his speech at the Royal Academy of Medicine of the Valencian Community: “Medical expertise and art”. Some of the tables studied, and the diagnosis issued, are the following: Velázquez’s “El Niño de Vallecas”, in which he sees a case of congenital hypothyroidism or cretinism; “Magdalena Ventura”, by José de Ribera, a case of hirsutism; “Carlos II El hechizado”, by Juan Carreño de Miranda, a case of rickets, anemia (perhaps of malarial origin) and a more than possible intellectual deficit; “Inheritance” by Eduard Munch, a case of early-onset congenital syphilis (“the painter turned his attention to a baby with signs of macular rash and hydrocephalus, as well as poor general condition and the appearance of old age facies”); “Gilles” by Jean-Antonie Watteau, a case of pituitary adenoma with excessive secretion of growth hormone; etc.

“Opisthotonos” (1809) Charles Bell (surgeon), tetanus

“Opisthotonos” (1809) Charles Bell (surgeon), tetanus

Rodrigo Ayala Cárdenas in CulturaColectiva.com on November 7, 2017, does a similar exercise to identify pathologies in paintings that are part of art history (it seems to me that using the work of Alejandro Font de Mora without citing it), and refers to: “Cristina’s World” (1948) by Andrew Wyeth, in which you could see polio; Quentin Matssys “A Grotesque Old Woman or The Ugly Duchess” (1513), a case of Paget’s Disease; “Petrus Gonsalvus” (mid-Cinquecento), by an unknown author ―the portrait was part of the court of King Henry II of France―, a case of Ambras Syndrome or congenital universal hypertrichosis (it was not the only case of pathological representations in the Court, the king himself authorized Ambroise Paré to paint his wounded eye in a tournament to investigate how to cure it); Sir Charles Bell’s “Opisthotonos” (1809), a case of Tetanus; the self-portrait of William Utermohlen (2000), Alzheimer; etc.

Self portrait William Utermohlen (2000), Alzheimer

Self portrait William Utermohlen (2000), Alzheimer

In sharp contrast to this approach, when women have focused their attention on diseases, they have done so by setting their sights on the cure. In addition to the cases of art therapy, of which in La Posta we have had some examples, such as the case of the Cyanotype Workshop, by Silvia Giménez, including the Sintonía de Colores Workshop, by Tamara Guerrero, both included in the programming of LABi 02, 2018 ―the project of the Master in Photography, Art and Technique of the Polytechnic University of Valencia in collaboration with La Posta Foundation, which takes place every year (this year has been interrupted by the outbreak of the crisis of the coronavirus, although it is in his mind to transfer his activities to Instagram) [can be seen here; These activities coincided with others at the same time, all of them beneficiaries of the “Emergents. Social Innovation Strategy in the Territory” of the University of Valencia in collaboration with the Valencia City Council]; Even more recently, we would have to refer to the activity carried out by Paula Valero Comín “Put in question” (an activity to heal the spirit), within the program of “Silence” developed by Norberto Llopis Segarra in collaboration with Miguel Ángel Baixauli and La Posta Foundation, within the framework of “Variations on the map” curated by Angela Montesinos and Juan Luis Toboso for IVAM Produce [see here].

Pepa L. Poquet, “Puig de Randa”

Pepa L. Poquet, “Puig de Randa”

Although the closest relationship with the Art and Health movement has occurred through our participation in FICAE, the International Festival of Short Films and Art on Diseases, organized by the Art and Diseases Chair of the Faculty of Fine Arts in Valencia, superbly directed by Ricard Mamblona and Pepe Miralles. Four editions of FICAE were held between 2015 and 2018, with La Posta participating in the last two, as a parallel venue dedicated to artistic activities. In this context, La Posta hosted the conference-performance of Pepa L. Poquet in conversation with Pepe Miralles [CONVERSA(C)TIONS] “2009. Guillain-Barre”, addressing the experience of the Guillain-Barre syndrome, having as a common thread the work/process “El·lipsi”, which in some of its presentations has included the video-installation “Puig de Randa”, inspired by the mountain Mallorcan Puig de Randa, where the Cura Sanctuary is located. The following year, in the FICAE 4 edition in 2018, the atmosphere of the workshop “Bodies in Struggle” was reproduced in La Posta, which was offered for the first time within a set of activities that, under the same name, included conferences, meetings and an exhibition, all of which took place at Las Naves CCC, in Valencia, in January-February 2017. Given by Anaïs Florin and Eva Fernández, with the participation of Pepe Miralles: Conversa(c)tions: Artistic practice and visualization of silenced stories: the case of the BODIES IN FIGHT workshop.

Precisely, belonging to FICAE, in its 2nd edition, 2016, 從此過著幸福快樂的日子 (She moaned), 2015, 18′, by Guo Mao-Quan (normally the country where the film was produced would be added, Taiwan in this case, we don’t know exactly why). He obtained first prize in the fiction section. You can see it on the screen above.

Still from “She Moaned” (2015) 18′, by Guo Mao-Quan

Still from “She Moaned” (2015) 18′, by Guo Mao-Quan

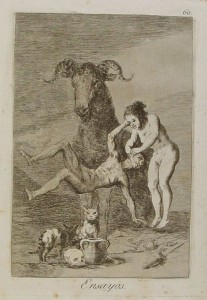

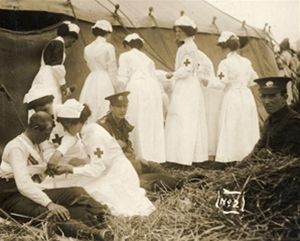

Women’s dedication to healing goes back a long way. Although society has not always been so grateful for its work. There was a time when they were burned in the public square. It was the time of the Inquisition. Accused in most cases of witchcraft. Although not all the women accused of witchcraft dedicated themselves to the cure, an important part of the cases did. Throughout the centuries of the witch hunt, the witchcraft indictment spanned countless “crimes”, from political subversion and religious heresy to immorality and blasphemy. But there are three main accusations that are repeated throughout the history of the persecution of witches, fundamentally in northern Europe. Above all, they were accused of all conceivable sexual crimes against men. Plain and simple, the charge of possessing female sexuality weighed on them. Second, they were accused of being organized. The third accusation, finally, was that they had magical powers over health, which could cause evil, but also that they had the ability to heal. They were often specifically accused of possessing medical and gynecological knowledge (Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English: Witches, midwives and nurses, a story of women healers, 1973).

Essays (1799), Francisco de Goya

Essays (1799), Francisco de Goya

Nora Ancarola “Ferida de Temps” [Time wound] (2015)

Nora Ancarola “Ferida de Temps” [Time wound] (2015)

Going back to the beginning of this text, when we said that it is the curatorial text that explains the theoretical framework in which the exhibition “Coronavirus, fear and courage” has been configured, and we have been describing the main items that frame this exhibition (iconography and symbolism; gender differences; dimensioning and formatting of an online exhibition…), all as if there were an insurmountable radical difference between theoretical aspects and their representation. But since this is not the case, we do not want to end without referring to a job that is a good example of this. This is the project “AntiKeres (The Healers or Curators)”, a work that Nora Ancarola and Marga Ximenez have been developing for a few years. It is a work in progress that is part of the Privacy Trilogy (together with “Sibila” and “Domus Áurea”), closely linked to the development of the MX Espai 1010 in Barcelona, that they have been managing since 1998, since it is a work documentary that has been nurtured with the contributions that have been made by the collaborators who have somehow participated in the work of MX Espai 1010. Through a letter, Nora Ancarola and Marga Ximenez asked for their testimonial contributions, in text format and image, focused on the issue of caring for the sick and elderly. In ancient Greece the Keres (singularly Ker) were evil spirits that had to be driven away. Called daughters of the night. Probably the antecedent of the idea of witches that would spread particularly in northern Europe a few centuries later. AntiKeres comes to oppose this negative idea by claiming the role of women who take care of people and the things we like. The development of the project has also included a series of video-interviews with these collaborators, who have made contributions of all kinds, such as sharing experiences, reading texts, etc. All this compilation of documents has been shown in different exhibition formats, in a succession of roaming art centers. We had the opportunity to learn about this project during the curatorial work of the exhibition “Museari: aesthetics of sexual diversity”, which took place in June-July 2016 in La Posta, in which Nora Ancarola exhibited her work “Ferida de Temps” [Time wound] (2015), on the impact of the passage of time on the skin and old age, which directly links disease and death, care and healing. We now bring the memory of all this, in this curatorial text on the exhibition “Coronavirus, fear and courage”, of which we said at the beginning that it comes to define the theoretical framework of it, as if theory and reality/life were separate things, because AntiKeres, being an archival work, fuses both things, confusing them.

Lola Donaire in AntiKeres video interviews

Lola Donaire in AntiKeres video interviews

Antoni Clapés’ contribution to AntiKeres

Antoni Clapés’ contribution to AntiKeres