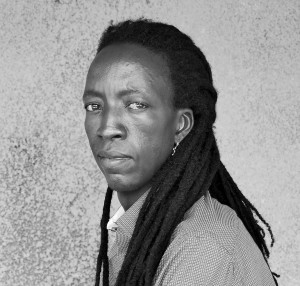

Nomwindé Vivien Sawadogo, born in 1981 in Dapoya, Ouagadougou (capital of Burkina Faso), emerges as a significant voice in contemporary African photography, challenging stereotypical representations.

Her work stands as a powerful counter-narrative to what academics such as Achille Mbembe have termed the “colonial gaze”: the reductionist representation of Africa through extreme poverty or tourist-oriented exoticism, the colonial gaze not only affects how Africa is seen from the outside, but has also influenced how Africans see themselves, creating what he terms a “colonization of consciousness”.

Sawadogo’s artistic approach is fundamentally rooted in what he calls “testimony”: a documentary style that seeks to capture the authentic everyday life of African communities. His work aligns with the camera’s ability to document reality and provide a creative interpretation of that reality. Through his lens, Sawadogo presents an Africa that exists beyond the binary of suffering or safari, revealing instead the rich tapestry of everyday life and cultural heritage.

One of the distinctive aspects of his work is his focus on ethnic scarification and ancestral practices, which he brilliantly compares to contemporary youth culture’s adoption of tattoos and piercings. This comparative approach echoes anthropologist Mary Douglas’ theories on body modification as a form of social communication and cultural continuity. By drawing these parallels, Sawadogo creates a visual dialogue between tradition and modernity, challenging the notion that these elements exist in opposition to one another.

He brings attention to often overlooked subjects—artisans, gold miners, dolotières [traditional brewers], and domestic workers— and this way of seeing challenges dominant narratives. His documentation of these individuals, along with decaying cultural sites and monuments, serves not only as a historical record but as an affirmation of cultural dignity and preservation.

What sets Sawadogo’s work apart is his ability to capture what he describes as “magical moments of life” – instances where reality and dreams intertwine. This approach aligns with the concept of “magical realism” in the visual arts, where the extraordinary is found within the ordinary. His photography becomes a platform for what he imagines as a “party” – a celebration where educated and uneducated people, young and old, can gather around images to dream and build futures together.

Through his photos, Sawadogo reaches out to the viewer and creates a personal connection. His request for “ONE LOOK” becomes more than just a plea for attention; it transforms into an invitation to genuine engagement with African reality, one that goes beyond superficial or prejudiced opinions.

Sawadogo’s work represents a vital contribution to contemporary African photography, joining the ranks of photographers such as Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta, who have worked to present Africa through African eyes. His photography serves not only as documentation but as a bridge between past and present, tradition and modernity, reality and aspiration, offering a nuanced and dignified portrait of African life that challenges prevailing stereotypes while celebrating the continent’s rich cultural heritage.

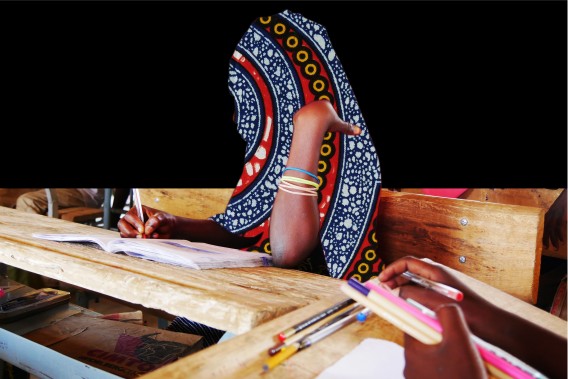

For the presentation of his work at La Posta Foundation we have selected a series that is particularly striking because the human figures, usually women, have been replaced by designs printed on fabrics typical of the Burkina Faso industry. Under the appearance of a collage composition, the author achieves the objectives we have referred to, breaking the clichés we are used to in representations of Africa, poverty or exoticism, without having to resort to other types of stereotypical images, such as those of the centre of the capital Ouagadougou, which seek to reproduce the images of the centre of any other capital in Africa or on any other continent. This breaking of clichés has a double direction: on the one hand, in relation to the representation of reality, which, without ceasing to be so, because there is nothing more real in the imagination of Burkina Faso than those prints on fabric, the composition made by Sawadogo is capable of generating another type of images that elevate the role given to human intervention in the construction of these images, and, on the other hand, the faces disappear, which as far as we know (as told, for example, by the protagonists of the film “Anunciaron tormenta” [Storm announced], 2020, by Javier Fernández Vázquez [member of the collective Los Hijos], about the events that took place in the Spanish colony of Equatorial Guinea in 1904), the protagonists live it as an unauthorized appropriation, after an experience of racialization of the image itself, so they didn’t want his image to appear in the film, only his voiceover. A whole declaration of principles in an image that is apparently so simple, which we present as if it were a postcard that the author sends to the world, reinforcing that idea of a message, because there is no more powerful repository of memory than a postcard.