Our architectural heritage is an element of cultural identity and of great collective wealth. The study of it must be important for the dissemination, knowledge and enjoyment of future generations. There are many interesting buildings in the city of Valencia that do not have an adequate study. In the same way it happens with a large number of architects, with works of great importance in those years, who do not have their own monograph.

The Second Republic had a very specific influence and was a great boost towards achieving the country’s architectural and urban modernity, conditioned by new materials or construction techniques and new social needs. The end of the war brought with it, in many aspects, the elimination of all traces of modernity in the country’s architecture. The decade of the forties was determined by the political isolation and the economic autarky of the Franco regime. These factors caused a standstill in Spanish productive activity and a shortage of consumer goods.

Architectural renovation efforts were relegated by the Franco regime. The development of rationalist architecture, which had appeared in the last years of the Republic, was almost symbolic after the Civil War, especially in the official discourse. Spanish architecture moved towards the formulation of its own national style, with an eye toward imperial architecture. It is a return to classicist traditionalism of an academic sign, a traditionalist art with historicist, regionalist or eclectic elements. Madrid will be the showcase for this new national architecture at the service of the institutions.

Lluís Bonet Garí, Life Bank, 1950, Barcelona. Source: Milerenda

Lluís Bonet Garí, Life Bank, 1950, Barcelona. Source: Milerenda

In the 1950s, eclectic historicism evolved towards a more modern style, coinciding with the end of autarky and the opening to the exterior. The progressive implementation of this style will be accompanied by the importation of new materials and construction techniques. There is also a return to the rationalist style by some architects. The reasons that explain this openness have their origin in the weak situation of the national economy, forced to request international bank credits and to liberalize imports.

Within Spanish architecture there is a debate about the national style and the opening towards new styles or currents. The demands in favor of architectural renovation are reflected in the Barcelona Group R (1951-1961) or in the Alhambra Manifesto (1953). In 1967 the Valencia School of Architecture was created, at first as a subsidiary of the Barcelona School, although it would soon have its own autonomy. They are also the years of the beginning of development architecture and the creation of the great Spanish construction companies.

Social policy becomes the main propaganda component of the regime to build the idea of national community among the Spanish. Housing appears as one of the fundamental pillars of that system and an effective propaganda tool in promoting the Franco regime. This policy will leave its influence on the social and developmental context of the cities, having a series of consequences on the landscape and their surroundings. Among the factors that determine this expansionist influence, and also the rapid implementation of social housing in Spain, is the definitive emigration leap from the countryside to the city by thousands of people in a progressive and constant course, the conception of the city as a macrocity or the different public policies.

The public housing policy will leave its influence on the social and developmental context of the cities, having a series of consequences on the landscape and their environment. Among the factors that determine this expansionist influence, and also the rapid implementation of social housing in Spain, is the definitive emigration leap from the countryside to the city by thousands of people in a progressive and constant course, the conception of the city as a macrourbe or the different public policies.

Some precedents for social housing can be found in some European countries such as the Netherlands, Germany or Austria. Paradigmatic examples are the höfe present in Vienna, the hofjes in Amsterdam or the Fuggerei complex in Augsburg. The development and characteristics of these constructions are determined by factors such as their location, the size of the plot or the materials used.

We can highlight two periods in the construction of social housing in Spain. On the one hand, a period between 1939 and 1954, with protected and bonuses housing. The houses used to be low-rise blocks, with a block patio and were built in the areas close to the expansion. On the other, a period between 1955 and 1963, with limited income housing. They had more means and qualities than the previous ones and were built in a neorationalist style, already intertwining some precepts of modern architecture.

The new regime, after the war, will promote a series of laws or plans that will try to regulate the housing market. In 1939 the National Housing Institute (INV) was created and the Protected Housing Law was approved. This law promoted social housing based on a series of tax exemptions or advances and created the figure of social promoters, that is, public and union institutions. Although later modifications extended this range to cooperatives or savings banks. That same law will be reformulated in 1944 with the Subsidized Housing Law, after not having given the expected results. Among the main novelties of the law is the expansion of the middle class strip that could take advantage of it and the granting of indirect loans to individuals at low interest and a long-term maturity through private promoters.

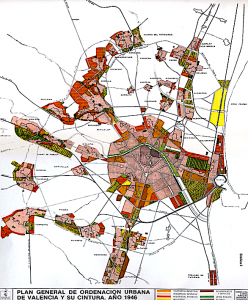

General Plan of Valencia and its Belt of 1946

General Plan of Valencia and its Belt of 1946

In Valencia, the General Planning Plan for Valencia and its Belt was promulgated in 1946, the first comprehensive urban approach for the city. The plan tried to rationalize growth, promoting it from a radiocentric scheme where the surrounding municipalities would absorb a large part of that growth. The growth of the city itself would be done through the orchard. The plan was somewhat ineffective due to the lack of resources and instruments to carry it out.

For this reason, the Greater Valencia Administrative Corporation was created in 1949, an administrative entity with the objective of controlling the planning and urban growth of the city of Valencia and its region, as well as the execution of the General Plan.

Between 1944 and 1954 a boost was given to the First Housing Plan. It will be the first planning attempt in the reconstruction and grouping of the different types of housing. In addition, in 1954 the Limited Income Housing Law was promoted, ratifying the family as a subject of social housing policy and giving lasting regulation to the market. The National Housing Council, the body in charge of coordinating housing policies, is also created. In those years the National Housing Institute will carry out an extensive constructive policy.

The National Housing Plan, developed between 1956 and 1960, is one of the first planning attempts in the management of public housing aid. It approved the limited and subsidized income housing regimes, in a balance between public and private action. Another law that gave a great boost to construction is the Land Law of 1956. Real estate interests prevailed over the Administrations, elevating planning to a fundamental element, that is, the use of the land over the social function of the property. It also established the legal status of the land and reserved the capital gains to the owners.

The State will definitively institutionalize the problem, creating in 1957 the Ministry of Housing, a resource management body to carry out public policies in a balance of financial and material means. A series of laws and legislative changes for the promotion of social housing were also drafted. Among them is the Horizontal Property Law of 1960, which involved a new financing system for the execution of different urban actions. The law reinforced the right to dispose of a mortgage with the purpose of encouraging the purchase of a home in the form of urban property and introduced the figure of several agents. These agents are the buyer, who financed the purchase with his savings, the owner of the real estate, and the builder.

The owner could reach an agreement with the builder, or vice versa, regarding the occupation of the plot in exchange for a part of the work to be built. For the financing of the future owner, a new system was enabled, the registration of the declaration of new work in the Property Registry before the construction of the building, on which the mortgage was made or constituted. The Officially Protected Housing (V.P.O.) granted the guarantee to be able to access this financing system. In addition, with the law the right of first refusal and retraction of the community members in horizontal property by floors disappeared.

The new National Housing Plan will arrive between 1961 and 1976. It focused mainly on free-regime housing, leaving aside those with limited or social income, and promoted the liberalization of land for the benefit of private developers, among other measures.

The flood of 1957 supposes the modification of the General Plan and the approval of a new one, the Plan of Valencia and its belt adapted to the South solution. The South Plan diverted the course of the Turia River and proposed a profound reform of the roads, collectors, transport and rail links in the city. That year the Flood Plan of the Ministry of Housing was approved, which promoted the construction of some 2,500 social-type homes, managed by the National Housing Institute, by the Limited Income Law and by the Home Union Work.

The General Plan of 1966 maintained the radiocentric structure of the city and provided for the growth of the city’s territory from the extension of urban land, which was doubled. In addition, towards an extensive road proposal and elimination of the railway belt and level crossings. Another consequence of the plan will be the permissive urban legislation regarding the demolition and construction of new buildings, often raising the average height of the historic center.

The exhibition “25 Years of Modern Architecture in Valencia (1950-1975)” reflects on the different ways or ideas of conceiving urban planning or the architecture of the city from contemporary thought, making the visitor witness to the set of transformative changes produced in the modern society of that quarter century. The exhibition, curated by Alejandro Chust, art historian and professional specialized in the field of Cultural Heritage, tries to synthesize the architecture of that quarter of a century, in its diversity of styles, functions and construction procedures, through some architectural examples or relevant housing groups, both public and private development. The selection has been made based on stylistic, typological and chronological criteria. Everything to compile some of the main architectural currents of those years that will serve as a guide to create a synthesis of the architecture of those years and go through the main changes in housing and urban planning that occurred in the city of Valencia throughout the third quarter. twentieth century.

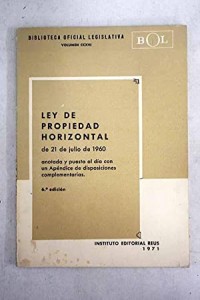

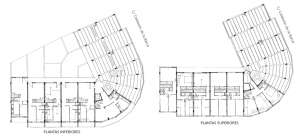

Residential Group Commercial Agents Section F

Residential Group Commercial Agents Section F

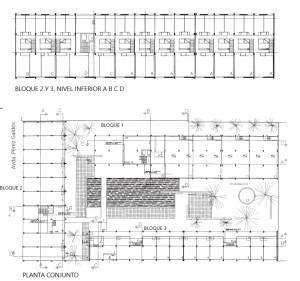

Marqués de Valterra Residential Group

Marqués de Valterra Residential Group

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

BLAT, Juan; CALDUCH, Juan; JORDA, Carmen; LLOPIS, Armando; PÉREZ IGUALADA, Javier; TEMES, Rafael. Lived stories. Groups of houses in Valencia 1900-1980. Valencia: Valencian Building Institute, 2016.

CANDELA OCHOTORENA, José. From the little apartment to the real estate bubble. The Falangist cultural heritage of home ownership, 1939-1959. Valencia: University of Valencia, 2019.

PASCUAL CERVERA, Guillem. Urban renewal and its legal regime. Valencia: Editorial Reus, 2013.

DAUKSIS ORTOLA, Sonia; LLOPIS ALONSO, Amando. Architecture of the 20th century in Valencia. Valencia: Editions Alfonso the Magnanimous, 2001.

JORDA SUCH, Carmen. 20 x 20. 20th century. Twenty works of modern architecture. Valencia: Official College of Architects of the Valencian Community, 1997.

MARIA MONTANER, Josep. The architecture of collective housing. Barcelona: Editorial Reverté, 2015.

PATUEL, Pascual. Valencian architecture and urbanism during the Franco regime (1939-1975). Valencia: University of Valencia, 2020.

PEÑIN, Alberto. Valencia 1874-1959: City, Architecture and Architects. Valencia: Higher Technical School of Architecture, 1978.

SANCHEZ MUNOZ, David. Architecture and urban space in Valencia, 1939-1957. Valencia: Valencia City Council, 2013.

TABERNER PASTOR, Francisco; LLOPIS ALONSO, Amando; MAYOR BLANQUER, Cristina; MERLO FUERTES, José Luis; ROS PASTOR, Ana. Valencia Architecture Guide. Valencia: Territorial College of Architects of Valencia, 2010.