This is a preview (a pre-announcement) of the exhibition that we were going to open this week (November 8, 2024): “Geomatics: Land | Law | Minerals”, by a multidisciplinary group of artists and other professionals dedicated to the territory, South Africans, a group directed by Jeannette Unite; an exhibition whose opening we have postponed given the situation we are experiencing with flooding and its consequences, especially in the southern part of the city of Valencia (beyond the new Turia riverbed) and in many other municipalities of l’Horta Sud district.

This is a project that received an honorable mention among those submitted to the “Art and Geology” call of 2023 for 2024 (the call in which the project “CaSO4.2H2O” [gypsum] by Raúl León was selected in first place ―with the participation of a large group of professionals related to this mineral―, which could be seen ―and participated in the conferences that took place in La Posta, between February 22 and March 16, 2024; see here).

The project by Jeannette Unite and her group caught the attention of the Board of Trustees of La Posta Foundation because, apart from the plastic issues (obviously), and building bridges with other disciplines and fields of professional action (which has to open new professional perspectives for artists; in this case, with architects, engineers and earth scientists), in addition, the material used as a base for the artistic interventions carried out, has been the protagonist of a bizarre story that perfectly sums up many of the concepts and values present in the work developed by this group of artists.

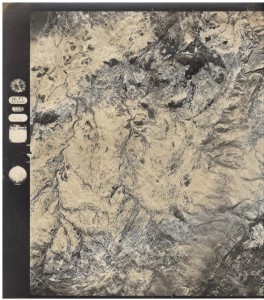

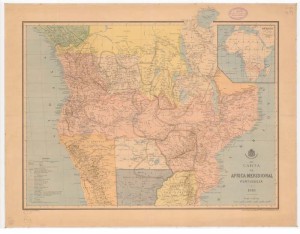

This basic material consists of aerial photographs taken by photogrammetric flights (the South African group had more than a hundred of them available for the development of its project), taken by the Spanish Army the year 1956, corresponding to mining operations (either active or in the exploration or research phase), located in South Africa. This material was, for a time, “classified” (probably as “reserved”, in view of the stamp on the back of one of these aerial photographs; although this stamp also refers to “secret”), until it was declassified in the eighties of the last century, at which time all this material was sent for teaching and research use to the University of Oxford (at that time there was a close relationship between this institution, specifically the Department of Earth Sciences, with Spain, in view of some letters to which we have been able to have access, sent by the coordinator of the group Jeannette Unite). At one point, Oxford University decided to send these photographs taken by photogrammetric flight to Nelson Mandela University in Cape Town, South Africa, in the early 1990s. Apparently, with no other objective than recycling them for other uses, so that this was no longer the initially attributed purpose of teaching and research in the field of cartography. However, due to the twists of fate, aerial photographs ended up retaining the purpose of research, now in the field of contemporary art, in which we are experiencing a renewed interest in maps, in the context of what has been called “the geographical turn” [Guasch, 2016, 161-204]; in short, interest returns in the artistic field for an image that was already conceptual before Conceptual Art.

The artificer of this recycling of found material, which, from the outset, is full of meaning in relation to several of the themes that make up the agenda of this art in the “geographical turn” (because it raises the question of colonial relations: What was the Spanish Army doing in South Africa developing an aerial photography campaign through photogrammetric flights, particularly of mines, of a reserved or secret nature?; in addition, the question of the environmental impact of the exploitation of mineral natural resources is raised, or its incidence on relations with neighbouring countries, given the demand for scarcely qualified labour ―in this regard, the tensions on the border with Zimbabwe, on the Limpopo River, are well known; on this issue see the magnificent work “Border Farm” (2007-2011, 30’), by Thenjiwe Nkosi and Meza Wezade (it has been analysed by the geographer Pauline Guinard: “The Art of (Re)Crossing the Border: The Border Farm Project in Maroi, South Africa”, in Public Art Encounters: Art, Space and Identity, edited by Martin Zebracki and Joni M. Palmer, Routledge, 2018, 161–179, in the field of what has been called the Art Geography). The woman behind the recycling of this aerial photographic material is Jeannette Unite, an artist and activist on several fronts, including the institutional one. She has been linked to Nelson Mandela University for years, and when she saw all this material she did not pass up the opportunity, developing a project based on the 30×30 matrix (corresponding to the measurements of the aforementioned aerial photographs), in whose structure the work of more and more artists has been incorporated, until reaching the first presentation of the project at the Turbine Art Fair in Johannesburg in June 2023.

If the source material, the aerial photographs mentioned above, is already of considerable interest, the artistic work carried out in its context, structure and inspiration is not far behind. The authors explain this in the video shown in the Screening above. In a kind of round table in the workshop where the group develops its work, Jean Dreyer and Lonwabo Kilani meets with Caroline Sohoe and Leszek Dobrovolsky of the Institute for Scientific Research on Earth Governance at Nelson Mandela University, meet, and address, among other issues, the assessment of the photographic material received, which serves as a basis for a set of reflections, which go beyond its current use in the field of cartography, where it is currently obsolete material, however, in the broader field of geomatics, it allows us to see how the first steps were taken in what we would later know as big data: a large amount of georeferenced information and the development of applications for its management that, partly due to their own operating structure, often do not expect the operator to ask any questions about it, but rather identify patterns in that set of information, which can lead to raising, once again, the question of a supposed objectivity in the representations made of all that information, a question in relation to which the participants in this round table are very skeptical, and proclaim the existence of a determined will. Which poses the question to us: would this exclude the possibility of aesthetics? In accordance with the thesis set forth by Arthur Schopenhauer (1818): The World as Will and Representation, §38, which appeals to the meaning of the word “aesthetic” as a form of sensorial cognition produced directly by the mere intermediation of our senses, without the participation of reason or will; ergo, if there is will, there could be no aesthetic appreciation.

However, although it might seem at first glance that aesthetics has been left out of the debate that is taking place in the round table, which the audiovisual above reports on, the truth is that this is not the case, and it re-emerges reformulated in a concept of enormous poetic charge, such as “solastalgia”. “Solastalgia is a hybrid neologism coined between 2003-2005 by the Australian activist, geographer and philosopher Glenn Albrecht (1953-) which is defined as the pain or affliction caused by loss, grief and sadness, accompanied by a feeling of abandonment and isolation, related to the present situation at home and in the area where a person lives; caused by the environmental impact that accompanies the massive pollution and ecological imbalance that has been produced by the destructive action of man (see Anthropocene). The term is composed of the Latin solacius, an adjective meaning “that consoles”, “that comforts”, derived from the verb solor (I console), solari (to console, to comfort…), and the Greek noun algos, which means “body pain”, “suffering”…, from which the use of the component -algia has become widespread, which indicates “pain” in medicine, as in the words cardialgia (heart pain), gastralgia (stomach pain), otalgia (ear pain), myalgia (muscle pain), astralgia (joint pain); but also “nostalgia” (from the Greek nostos, “return”), from which comes the sadness of being far away from people or places where we cannot return, or from the sad memory of something we lost, like that felt by an elderly person for the beautiful youth that will never return” [Online Castilian etymological dictionary https://etimologias.dechile.net/?solastalgia ].

So this group of artists that make up the Atlas | Mine project began working in the context of geomatics, an issue to which they have applied an enormous effort (for the presentation of their work at La Posta Foundation they even made a comparison of the tectonic plates in Africa and in Spain-Europe ―from which results, by the way, the singularity of the territory comprised in the Betic Mountain Range, with special seismic activity, in particular in Murcia and the Vega Baja district (Comunitat Valenciana), a consequence of the collision between the African and Eurasian tectonic plates; and, where the phenomenon of subduction between plates is changing direction, and if before it was the African plate that was subducted beneath the Eurasian plate, now it is the Eurasian plate that is subducted beneath the African plate―); They began with an in-depth study of geological issues, within the framework of a profound love for the earth, to end up incorporating into the debate the concept of solastalgia, like that generated by their artistic work that will undoubtedly stir up sensations within us.

Geomatics: Land | Law | Minerals

Round table: Geomatics and new cartographies in contemporary art