The Barda del Desierto Museum, that we have had the honor of presenting at Fundación La Posta, by Andrea Beltramo, is an open-air museum, in which works specially designed for that place are carried out and are influenced by its characteristics, as well as artistic residences and educational activities, it is located in the Alto Valle del Río Negro region, North Patagonia, Argentina. It is located near the place where the Neuquén and Limay rivers converge to give rise to the Negro River. A river that, together with the Colorado, a little further north, constituted for centuries an internal border in the emerging Argentine nation. We are, then, in a border territory, in many ways, and a landscape that shows us, like an open book, Argentina’s past.

Paul Claval, one of the reference cultural geographers, said that: “The observation of landscapes is enough to demonstrate the methods imagined by the different groups in order to achieve their insertion in nature” (Claval, 1995). Long before, Masao Adachi, from his cinematographic experience, had reached a similar conclusion, formulated in his “fukeiron” landscape theory, according to which the landscape is a reflection of the social and political conditions in which it is produced our existence, “the landscape reflects the image of the power of society”, some reflections that the filmmaker made on the occasion of the production of his film “A.K.A. Serial Killer” (made in 1969, could not be released until 1975). The landscape is, then, the trace of our insertion in the environment in order to develop our life and that of the community to which we belong, while reflecting the conditioning articulated by the society in which we live.

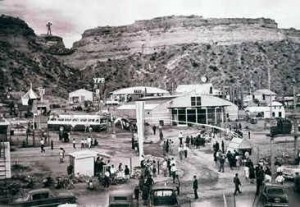

In the image, incipient urbanization in Villa Regina, settled mainly by Italian immigrants, with the Comahue Indian in the background (1964). Between the pavilions you can see the logo of the national oil company YPF.

And that is exactly what can be seen in the landscapes of the Alto Valle del Río Negro, where the Barda del Desierto Museum is located. It is, to use the expression coined by Robert Smithson, an entropic landscape, as he formulated it after his walks through Passaic, New Jersey (some walks documented even with photographs in his work “A tour of the monuments of Passaic, New Jersey”, 1967). The museum benefits from these landscapes to fulfill its function and to which it contributes with the story of its own existence and of the activities carried out by those who participate in its programs.

Canal de los Milicos, with untreated discharges.

Among the events that have marked this territory, there is one that stands out in a relevant way, such as the establishment of its irrigation system at the beginning of the 20th century. It is, as María Cecilia Danieli points out in “The ideological origins of the irrigation system of the Alto Valle del Río Negro and Neuquén, Patagonia, Argentina” (published in Scripta Nova, the Electronic Journal of Geography and Social Sciences, of the University of Barcelona, Nº. 2018, of August 1, 2006), of an action that had to serve for the colonization of this territory, mainly with foreign migrants, a vast operation of the new Argentine state that emerged from the independence of Spain. Because it must be taken into account that this territory was never effectively colonized by the Spanish. A colonization that was carried out later, as part of the process of building the Argentine nation, by enhancing the value of this territory, which had to attract emigrants and foreign capital, through the execution of a vast plan for the in irrigation of what was considered, within the national construction plan, as the desert, space for barbarians. In reality, these are arid steppe lands populated by indigenous people (mainly of the Mapuche ethnic group, although mixed with the Gününa Kune, whom they had previously assimilated), and gauchos (a multi-ethnic group of Creole origin ―probably including even Moorish immigrants―, semi-nomadic, who subsisted on the sale of wild cattle, with a reputation for criminals, took herds that they later sold to European expeditions, mainly French) and broken (“rotos”), the protagonists of the popular saying: “there is always a broken for a ripped”; the lowest step of the social structure.

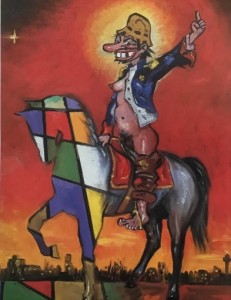

In the popular culture that has recreated the character of the “roto” [broken], mainly in Chile, although María Cecilia Danieli also refers to Argentina, in the landscape of Patagonia; he has always been represented as a man. The “rota” [women broken] was not known. So, the first transgression of Juan Dávila’s work: “Rota” (1996), was to represent him as a woman. For the rest, it is a representation that takes elements from the popular comic book character “Juan Verdejo”, who popularized the Topaze magazine since the thirties of the last century.

María Cecilia Danieli recounts in great detail the relationships between the approaches of the ruling classes, which are not limited to the capitalists of Buenos Aires, but also include politicians, military and ecclesiastical (who had considerable influence), and the different actions that take place on this territory from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century, in order to move the internal border existing in the idea of the Argentine nation, beyond the Colorado River, incorporating the Pampa and Patagonia into the nation ―while creating another imaginary interior border, the one that was going to separate the “gaucho” and the “roto” from the indigenous people―. It is fundamentally about irrigation works, but also containment of the avenues, before the floods of the Negro River. Especially devastating were the floods of 1900, which almost ruined all the plans that were being developed for this territory, in addition to some bad decision made in the planning and execution of the works. Some works executed mainly by Italian migrants. María Cecilia Daniele pays attention, even, to the legal formulas adopted to carry out this entire process, and how, when the enormous capital gains generated by the works in progress begin to be seen, the State opts for the acquisition of some of the land (some speak of nationalization), with the eviction of its occupants (migrant farmers from Europe), even of some character that we could classify as among the ruling classes, as is the case of Reverend Father Alejandro Stefenelli, founder of the school of agriculture, supporter of coexistence with the indigenous, instead of their eviction, and that could be annoying to the approaches that were making their way in the capital, dominated by the thought of Domingo Faustino Sarmiento (politician, writer, teacher, journalist, Argentine soldier and statesman, who would occupy the presidency between 1868 and 1874), which conceived the indigenous people as a non-society, savages, so that there was only room for their subjugation or extermination.

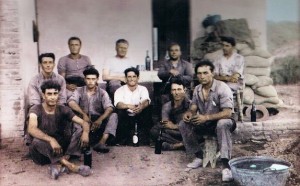

A crew of irrigation canal workers formed by Italian immigrants from the Tuscany region in 1924. Among others: Luigi Fedi, Gargino Gargini, Francesco Mungai, Bruneto Bonachi. Some of them could be evicted with the nationalization of lands decreed by the Argentine State.

The author we cited qualifies her work as “intellectual history”, but the truth is that, taking into account that she fixes her attention on the processes of transformation of the territory and the objects that this process generates, and not only the irrigation canals, but also that also pays attention to the regulating dikes, to deal with the floods of the river, the implantation of the colonies, the configuration of the farms (the “chacras”, the specific production model, in which the crops do not grow isolated, but rather grow “associated”, complementing each other), we are facing a work that can be described as cultural geography.

The “chacras” are the agricultural exploitation units, normally of an associative nature, with an easily identifiable footprint in the territory.

Mapuches currently in actions to claim a position in today’s Argentine society, whose articulation must necessarily occur through the recognition of rights, which is the political and legal culture in which we find ourselves.

Within cultural geography, the section dedicated to geology and peleontology is of considerable importance, because it helps us to understand that things were not always as we see them now, but that things evolve, there are changes, some of them of as great a magnitude as which meant the disappearance of the dinosaurs from the face of the earth.

Museo Paleontologico Municipal Ernesto Bachmann, in Neuquen, the most populous city in Patagonia and capital of a growing metropolitan area.

However, the element that dominates the landscape of the Alto Valle is the Negro River, which has a variable width that goes from 5 kilometers to 25 kilometers in Choele Choel. In reality, it is a riberbed resulting from periodic overflows, full of fluvial islands (some as large as Choele Choel, within which is the city of Luis Beltran, with 5,600 inhabitants), and abundant meanders that make up a territory with an alluvial soil made up of sediments that has given rise to enormously fertile lands.

Abandoned meanders or dead arms in the Negro river basin.

Children bathing in the Negro River, formerly known as the river of willows, due to the enormous number of weeping willows on its banks.

Above on the screen of this post you can see a documentary about the irrigation system of the Alto Valle del Río Negro, from the year 1926, which has been made public by nitratoargentino.org, a project of the Pablo Ducrós Hicken Film Museum, Buenos Aires. Licensed creative commons (reuse allowed).

Learn from the stone. Presentation of the Barda del Desierto Museum (North Patagonia)