The first thing that draws attention in the photographs that are exhibited in “Cross-border Motherhood” by Gabriela Rivera Lucero, is that the photographs show the traces of an intervention on them. The artist herself has explained that the negatives were introduced before their development in a liquid in which objects and vegetable plants related to the life experience of the photographed women had been bathed. There is a call to incorporate memories and images that tell us about other things that are beyond the image that is shown, as indications of something that cannot be seen but that can be sensed. With this, Gabriela’s work is part of a current of thought and work that seeks to discover the past in the small signs that appear before us, many times without having been summoned.

This artistic current has illustrious theorists, the most likely being Carlo Ginzburg, among whose output stands out his text “Clues” (which he himself included in a collection of texts: Myths, Emblems, Clues, 1990), where he was able to see the plastic part of issues that until then had remained merely written, forming part of history, if they had not remained in the world of unwritten knowledge.For his part, Ginzburg has claimed the know-how of Giovanni Morelli, who was the promoter of the new method for revealing authorship when these were questioned in old paintings, often unsigned, as an antecedent of his work.He proposed to focus attention on insignificant details, on what is not the first attention of a pictorial composition, because that is where a copyist will not pay much attention, and his true identity will be revealed.Morelli was an autodidact who trusted in intuition (that brain mechanism that is capable of processing infinite amounts of information in an instant to come up with a valid result, without it being possible to explain it).

Around the same time that Carlo Ginzburg was working on these issues, Günter Metken knew how to apply this thoughts to the organization of an exhibition that over the years has turned out to be fundamental: “Spurensicherung: Archäologie und Erinnerung” [Spurensicherung. Archeology and Memory], with works by Didier Bay, Christian Boltanski, Jürgen Brodwolf, Claudio Costa, Nikolaus Lang and Anne and Patrick Poirier, held in 1974 at the Kunstverein in Hamburg. Shortly after, Metken participated in the preparation of Documenta 6 (Kassel 1977), directed by Manfred Schneckenburger, in the Plastik Art/Environment working group (together with Jan van der Marck and Edward F. Fry), and all the artists mentioned repeated (except Didier Bay), as well as Dorothee von Windheim (whose work, by the way, constitutes an antecedent of the work of Patricia Gómez and Mª Jesús González). Later, when in 2001 Manfred Schneckenburger wrote in Art of the 20th century, from the Taschen publishing house, the part dedicated to “Sculpture”, would include a section on Spurensicherung ―which in the Spanish edition was translated as “Traces of memory”―, granting identity in the history of art to this artistic current.

In 1977 Gunter Metken published: Spurensicherung. Kunst als Anthropologie und Selbsterforschung. Fiktive Wissenschaften in der heutigen Kunst, DuMont, Köln 1977 [Spurensicherung. Art as anthropology and self-exploration. Fictional sciences in contemporary art. DuMont, Cologne 1977], which is the book in which he theorizes about the new artistic current, including, in addition to the artists who had participated in the 1974 exhibition, at the Kunstverein in Hamburg, he also refers to the works of Charles Simonds, Nancy Graves, Paul-Armand Gette, Jochen Gerz and others.

In the same field of artistic and theoretical activity, aimed at making a kind of understanding of the past based on the observation of small traces left by the evolution of history, they were taking place on the same dates in the other hemisphere of the planet, in Latin America, a development of its own, according to Gabriel Mario Vélez Salazar in “Photography as a tool for magical thinking”, ISBN: 84-669-2465-5, doctoral thesis read at the Complutense University of Madrid, in 2004. Gabriel Mario Vélez explains that photography has an informational or documentary component, but on occasions it can also be a magical device, in that it “can produce an emotional shock, prior to discursive elaboration, which colonizes our consciousness in the form of discomfort. By transcending the informational dimension and becoming a lacerating instrument, it operates as a tool of magical thinking” (Vélez, 2004, 281). And he gives as examples, the works of a large group of Latin American photographers of all times, from the origin of photography (although it also includes some Anglo-Saxon and French, particularly from the early days of photography). “The European introduced [in Latin America] a Christianity contaminated with witches and horrors. The Indian and the Negro the animation of natural forces. Consequently, magic permeated from the very base all possible interpretations of the world. […] Completing the picture, while Europeans (in Europe in the mid-nineteenth century) faced the modern project and its intense demystifying program, in Latin America, after the different independence processes, internal conflicts cut off access to the different vanguards. Consequently, the premodern schemes that had been established with miscegenation were maintained and modernization policies were incorporated in a fragmented and chaotic manner. Therefore, without the possibility of taking root in any coherent project. Under the protection of a situation of successive crises, magical thinking in Latin America survived to contaminate everything. In this way, the extraordinary does not burst in to fracture reality, but is incorporated as something that is also part of it and therefore cannot be denied” (Vélez, 2004, 282-283).

Martín Chambi: “Marriage of convenience”, 1926. One of the examples collected by Gabriel Mario Vélez Salazar in the Photographic Album of his thesis “Photography as a tool for magical thinking”.

In these coordinates, in the middle of the 20th century, Magical Realism burst onto the Latin American (and global) cultural scene. Many other artistic expressions wanted to get closer to him, many times in order to try to take advantage of the pull of what was called “the Latin American boom.” “In any case, with movement characteristics, consensus has only been achieved to refer to what happened in the literature. The same must be said of photography. Since its appearance on the continent, there has never been a grouping that in any way articulates itself around an objective or a program. Therefore, although it is true that there is a Latin American photograph due to the origin of the authors, to be rigorous, they should be referred to as a group of individualities” (Vélez, 2004, 283-284) [Gabriel Mario Vélez Salazar is in current teaching at the University of Antioquia (Dean of the Faculty of Arts), Medellín, and in the Los Andes University, Bogotá, Colombia; as well as an active artist].

- Photography as a magical device

- Author: Gabriel Mario Velez Salazar

- Publisher: University of Medellin

- Edition: First, 2006

- Format: Book

- Rustic, 16.5 x 22.5 cm

- 260 Pages

- Weight: 0.38 Kg

- ISBN: 9589785468

At La Posta Foundation we have paid significant attention to Latin American photography and, especially, to Chilean photography. You can follow the hashtag #FOTOGRAFIACHILEValencia (especially on facebook). And among other activities, we disseminated on our website the documentary “8 PHOTOGRAPHERS” (Chileans), from 2012, which reports on the work of Tomás Munita, Javier Godoy, Jorge Brantmayer, Nicolás Wormull, Alejandro Olivares, Andrés Figueroa, Rodrigo Gómez Rovira and Claudio Perez. http://fundacionlaposta.org/en/media/8-fotografos-chilenos/

The aforementioned documentary refers to a group of Chilean photographers that is highly representative of the current art scene, and of whom it can be said, as Gabriel Mario Vélez Salazar concludes in his thesis, referring to Latin American photography in general, that it is a set of individualities, in the opposite sense, a joint manifesto has not been produced proclaiming some objectives that allow us to speak of a movement or current. In spite of which, it is possible to find in the work of these photographers some traces of something similar to what Carlo Ginzburg was looking for: to have a revelation, to find in the insignificant the explanation of something larger that would otherwise be unfathomable (Ginzburg refers, among other elements, to the fingerprint, which would speak to us from the unique skin of an unrepeatable subject, what the human being is like, about the generality of himself and even of the species). This issue is addressed, for example, among the artists included in the aforementioned documentary, in a work by Jorge Brantmayer, in which he makes portraits of people who have suffered violence (they go to look for them in a women’s prison), and notes how a face can put on the table a whole social problem: skin care, hair oiliness… And Andrés Figueroa also addresses the same issue, in a very penetrating way, who fixes his attention on some dancers from indigenous peoples to the north of Chile, more specifically in the costumes they use for their dances: “…in the case of the dancers there is a whole tradition, a culture embedded in the costumes, symbols of Aymara or indigenous peoples, also mixed with the Catholic, which has a whole cultural load that I am interested in rescuing, on that side is my anthropological, archaeological interest, in rescuing all of the culture, of the miscegenation that exists in the costumes. I realized that this religious festivals it was bigger than I thought, a way of life of many people was involved, on which a whole system of social protection was sustained, a whole community system and a trench of survival of a somewhat difficult society” [Figueroa, 21’55”].

Objects (of missing). Claudio Pérez [screenshot 30’19”]

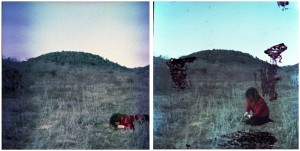

There are traces of all this in Gabriela Rivera Lucero’s project “Cross-border Motherhood”. In addition to the traces left on the photographic negative by the action of substances directly related to the biography of the photographed women ―traces that are offered to us with their best view and testimony in the reproductions of the photographs made on canvas―, which they force us to question ourselves (what part of their lives do those colors obtained, those glazes, tell us about? What do the applied substances smell like?…); In addition, these photographs taken with great personal proximity by the artist to migrant women in rural environments in the interior of the Valencian Community, show us, with indicative signs, the part of the culture that they brought with them when migrating. So it happens in the case of Manal, showing her kaftans, which she saves for the most important days, like the day she was photographed. As in the case of Maru, interpreting her particular “murga”, with the costume that she has made herself, at the foot of the castle of Azuebar (Castellón, Spain), a dance that reminds her of her Argentina of origin, although she did not learn it there, but here, a way of integrating by remembering her roots, with the strength that motherhood gives her. Because these photos speak of the strength of motherhood, even though her daughters do not appear in the photos. This detail should be highlighted, because for Maru, showing her motherhood is not showing her daughters, but rather showing the strength that motherhood has given her, which “makes her able to cope with everything, even the slightest crazy idea”, a state of mind that It has led, for example, to dance the “murga” in the castle of Azuebar, on the edge of the precipice, looking at infinity.

Maru interpreting her “murga” with the costume that she has made herself, at the foot of the castle of Azuebar (Castellón, Spain), on the same precipice, looking into infinity.

There is in these actions a point of spell, of wanting to bring to oneself the strength from where it comes, from who we were. This is very evident in some photographs that, as a climax, show us the artist herself in a kind of ritual in which she asks the earth, in intimate connection with her, that its strength and substance lead her through the path of knowledge in this doing composing the “Cross-border Motherhood”.