It is estimated that on the planet there is no more than 3.5% of the population that changes their place of residence during their lifetime by changing countries, which is known as migrants. That is, human beings are extremely sedentary. On the other hand, although a significant part of that percentage have come to Europe (64 million, a quarter), the truth is that, in relative terms, compared to the existing population in Europe, these are very low figures (the 64 million cited when they barely represent 8.60% of the European population ―741 million―).

But here we are not going to talk about migration in the strict sense. Crouched behind this phenomenon is another that questions us in a more pressing way, because it does not have a usual explanation of a social, economic or political nature. It is about nomadic life, which seems like the echo of a time before the organization of social life around paid work.

Although nomadic life partially coincides with migrant people, it is not always the case. Nomadic life has its own characterizing profile. Beyond the paradigmatic case of the gypsies —who, still settled, do not abandon their nomadic customs—, small groups of the population live with us who have never been integrated into our social and work organization and who do not come from outside, but always They were here. In addition, they come to deny that they are a way of life from the past, because it is a way of life that is renewed, that has gone through the entire rationalization process that the Enlightenment launched, resulting in immunity to its effects.

The nomadic life to which we refer is both that of the human beings who appear portrayed in the works exhibited in this exhibition, and that of the artists who practice it to capture their lives. Immersed as we are in the idea that art must be involved in life to fulfill its function, it could not be otherwise.

The works of Joost Conijn “Siddieqa, Firdaus, Abdallah, Soelayman, Moestafa, Hawwa en Dzoel-kifl” (40′, 2004); Denis Ponté: from the series “Nomadic Community Garden” (2018) and “Left for Dead” (1994), photography, in London and New York; Toni Serra aka Abu Ali: “Al Barzaj” [“Between Worlds”], video, in Marrakesh, 13’, 2010; Ulrike von Gültlingen “Hohrodberg” (Alsace, 2021) and the photographs of Enrique Gil Bazán made for the study of the stone sea of Arroyo Cerezo, in Rincón de Ademuz (Valencian Community), they are exhibited in this exhibition.

“Siddieqa, Firdaus, Abdallah, Soelayman, Moestafa, Hawwa in Dzoel-kifl” (40′, 2004), Joost Conijn

As for Joost Conijn’s work “Siddieqa, Firdaus, Abdallah, Soelayman, Moestafa, Hawwa en Dzoel-kifl” (40′, 2004), which could be seen at the 2012 Paris Triennale, “Intense Proximité”, in the Palais de Tokio, it is a video work that shows the life of a group of children in a wasteland on the outskirts of Amsterdam. Although the first thing that stands out is that during the whole day there is little presence of their parents, and they are not abandoned, but this is not the most relevant, but the fact that, although they are there, they could be anywhere else. Nothing suggests that this is his permanent residence, and not because it is precarious. It’s all extremely provisional. The children build their instruments for the game with what they find in their path. But they are there doing it with great intensity, with a great mastery of space, not as someone who is uprooted. In short, as nomads.

Claire Staebler says, in the 2012 Paris Triennale Exhibition Guide “Intense proximitè”, where this audiovisual was shown under specific conditions (in the expansion in the basement of the Palais de Tokio): “Conijn puts his camera and it simply takes that childish energy from the source, forcefully and simply questioning cultural belonging, religion and authority, while pushing the boundaries of tolerance and integration.” Indeed, the borders of tolerance are being forced. These kinds of works that make life the raw material for an artistic experience inevitably raise issues of legitimacy (if not directly legal issues), particularly in relation to the use of the lives and images of others. So much so ―that there is always that tension and those problems― that, according to the website of the Franz Hall Museum, in Harlem (The Netherlands), in whose collection is the Joost Conijn audiovisual that we commented: “Not long after the premiere of the film, the politicians in Amsterdam would intervene and Bureau Jeugdzorg would take the children from their father and take them out of their home.”

“Nomadic Community Garden” (2018) and “Left for Dead” (1994), Denis Ponté

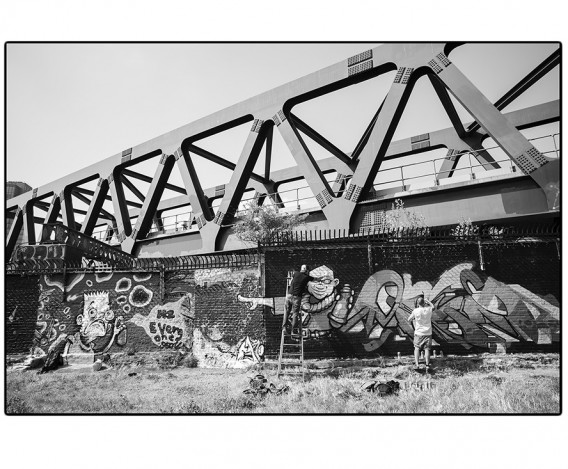

As regards the work of Denis Ponté, it stops at the Nomadic Community Garden in London and brings us closer to a community experience that reminds us, for a moment, of the Christiania of Copenhagen, but its most important virtue is that it highlights the persistence in the time of forms of life in common whose organization does not revolve around paid work, as is the case of the community —whose members are constantly renewed, but which remains as such— of graffiti artists and all kinds of artists existing in Nomadic Community Garden.

From another series by Denis Ponté “Left for Dead”, made in New York in 1994, we have selected a photograph in which the urban space of nomadic life appears in the foreground. Both in this and in the other photographs (and especially the one of the graffiti artists under the bridge), it becomes clear that urban life takes place in urban spaces that are spoiled, without a clear use, as is the case of the spaces that appear under the bridges of urban infrastructures, or in the large paved surfaces that appear in cities that are neither sidewalks nor squares, the result of the application of the standards of empty space proportional to the buildable area, which when the buildable area grows a lot, gives give rise to empty spaces without a clear use, which, together with the constant decrease in the number of pedestrians because mobility has been replaced by transport by private vehicle, especially in the suburbs, ends up creating the perfect scenario for the development of the nomadic life.

“Al Barzaj” [“Between Worlds”], Marrakesh, 2010, 13’, Toni Serra aka Abu Ali

The title of this work is already very expressive of its content: “Al Barzaj” [“Between Worlds”], wandering souls and bodies between different levels of consciousness, between different sites and places. Geography for deterritorialized, between two shores. In a comment on this audiovisual we can read: “A walk between worlds. Wandering through complex paths around light and darkness, where the gaze is constantly surprised and adapted by the contrast. Between blindness and maximum illumination. through the interiors of any Moroccan city where people and objects appear, just as quickly as they disappear. An oscillating transit between life and death on the margins of anonymous homes” [from the blog Tam Tam Press, from León, giving an account of the activities of the MUSAC of León with Toni Serra / Abu Ali]. “Al Barzaj” [“Between Worlds”] is a work that creates its own format, halfway between video-art and creative documentary, blending autobiographical aspects of the creator himself with the specific circumstances in Marrakesh, and both, both memory as places, showing wanderings and nomadism.

“Hohrodberg”, 2021, Ulrike von Gültlingen

Has anyone ever stopped to think what a nomadic landscape can be like? From the outset, it seems that the ideas of their own landscape and nomadic life would be at odds. Taking into account that one of the main characteristics of nomadic life is its mobility, it seems that there would not be a specific landscape, but rather, on the contrary, it would necessarily be a changing landscape. However, there is something in Ulrike von Gültlingen’s photographs that makes us think of the idea that we are before the image of what could be a landscape of nomadic life. We had that impression when looking at the series of photographs “Glaswaldsee” that were shown at La Posta Foundation in the collective exhibition “Inflexive Speeches”, organized by Red Nómade and Yvonne Andreini [see here ]

In the series “Hohrodberg”, 2021, constructions appear that could serve as a room. Originally built for war, they may later have served as a shelter for shepherds, refugees, hikers, etc. Nomadic life needs habitats here and there, in which to rest on the road. Thus, in nomadic life there is landscape and there are dwellings. One could even speak of a geography of nomadic life. It has been done by the researcher Michael Frachetti, from the University of Washington. He argues that nomadic life shaped the geography of the Silk Road in the Central Asian highlands. There, the typical shelter for the caravans that take the cattle looking for the best pastures is the Caravasar. La Posta is a Caravanserai. A place to arrive, rest, think, and follow the path. You can also find it in Alsace, in Hohrodberg. The nomads are among us, even if we do not see them.

The sea of stones of Arroyo Cerezo (Rincón de Ademuz), Enrique Gil Bazán

But we don’t have to go that far to find the landscapes of nomadic life. Here near Valencia we have an overwhelming one: the sea of stones between the towns of Arroyo Cerezo (Rincón de Ademuz) and Alobras (Teruel). That sea of stones has been studied by Enrique Gil Bazán.

It is called a sea of stones due to the fact that these lands are made up of marine deposits made when these lands were below sea level millions of years ago. In fact, fossilized marine reefs have been identified in lower soil strata, visible in a pit opened in the earth by the flow of the Cerezo stream.

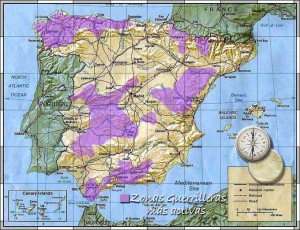

This sea of stones is part of the plateau of the Sierra de Albarracín, the Montes Universales, the Sierra de Gúdar. It is the territory of the Maquis (the anti-Franco guerrilla that extended its activities from the Civil War of 1936-1939 until the end of the 50s of the last century); the territory also of the Carlists (the supporters of the brother of Ferdinand VII in conflict with his successor Isabel I ―and before the Regent María Cristina―; conservatives at war against the liberals, a war that lasted in three episodes, from 1833 to 1876 , the time of the disentailment of the assets of the Catholic Church and the disengagement of noble estates).

Most active guerrilla zones during the Franco regime

Most active guerrilla zones during the Franco regime

We are before a territory that has known wanderings, nomadism and vagabondage. In that territory, whose best identification is precisely by looking at the delimitation of the AGLA (Guerrilla Aggrupation of Levante and Aragón) of the Maquis, it is the territory in which The Shepherdess / The Wolf of the Maestrazgo, who was known by both names, carried out his activities (today we would call it intersex, so it has sometimes been called a hermaphrodite), we have learned of its existence from the novel by Alicia Giménez Bartlett: Where nobody finds you (2011).

The Shepherdess / The Wolf of the Maestrazgo

The Shepherdess / The Wolf of the Maestrazgo

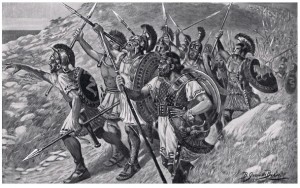

This is the perfect landscape for a contextualized reading of Xenophon’s Anabasis, the story of other wanderers. The expedition of the Ten Thousand that in 401 BC left the Aeolian and crossed the Anatolian peninsula to fight under the command of Cyrus the Younger, who intended to seize the throne from his brother Artaxerxes II, the Great King of Persia. The battle took place at Cunaxa, the present site of Tell Kuneise, west of Baghdad. Although the battle was won by the army of Cyrus the Younger, in alliance with the professional Greek army, the fact is that after the battle it was known that Cyrus the Younger had died, and his troops went in disarray to the enemy side of Artaxerxes II, leaving the army of the Greeks abandoned on hostile land. These then undertake an uncertain path back, in the midst of considerable disorientation, since their generals had been killed in a trap prepared by the army of Artaxerxes II. It is at this point that Xenophon takes charge of the return expedition, recounting the adventure on his return home. On the way back they crossed the territories of Mesopotamia and historical Armenia, traveling along the banks of the Euphrates to Lake Van and then to the Black Sea, when they would exclaim the well-known: “Thalassa, Thalassa” (“The sea, the sea”).

Thalassa! Thalassa! (The sea! The Sea!), engraving of Berdard Granville Baker, 1901.

Thalassa! Thalassa! (The sea! The Sea!), engraving of Berdard Granville Baker, 1901.

“Thalassa, Thalassa. Rückkehr zum meer” (1994), Bogdan Dumitrescu

“Thalassa, Thalassa. Rückkehr zum meer” (1994), Bogdan Dumitrescu

The story of the expedition of the Ten Thousand has been made into a movie on several occasions, and has inspired many other films, such as that by Eric Baudelaire: “L’anabase de May et Fusako Shigenobu, Masao Adachi et 27 années sans images”, 66′, 2011, but we want remember now precisely the movie “Thalassa, Thalassa. Rückkehr zum meer” (1994), by Bogdan Dumitrescu, which tells the story of a group of boys and a girl who find and steal a convertible Jaguar and decide to drive to the sea (the Black Sea). What starts out as a joke deteriorates into a pretty grueling ride. Which brings us back precisely to the beginning of this itinerary of the exhibition “The Nomadic Life”, when we started talking about the film “Siddieqa, Firdaus, Abdallah, Soelayman, Moestafa, Hawwa in Dzoel-kifl” by Joost Conijn.

THE AUTHORS

Joost Conijn (1971, Amsterdam)

His activity unfolds halfway between technology and art. He is an inventor and adventurer. Among other things, he has built airplanes, using bicycle parts. The first crashed shortly after takeoff, but with the second it traveled to Kenya. He has toured various countries in Eastern Europe with a vehicle made of wood that runs on gas generated by the vehicle itself. He has made movies narrating these adventures. Among others, one about his trip by bicycle through Morocco with two friends.

His works and vestiges of his adventures and his inventions are in the collections of the Franz Hall Museum in Harlem (The Netherlands) and in the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen in Rotterdam. His works and experiences have been shown in art spaces around the world: Royal Athenaeum of Antwerp, in 2017; Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art, in 2015; 13th Istanbul Biennial and Biennale of Sydney in 2014; Museum Volkenkunden Leiden (NL) in 2013; Kröller-Müller “Art Cars” Utrecht and Triennale de Paris “Intense Proximité” in 2012; Matadero Madrid in 2009; WORLD MAP ’08 Pamplona in 2008; Cobra Museum (Solo exhibition), Amstelveen (NL) in 2005; Miro Foundation (Solo exhibition), Barcelona, in 2005; etc.

Joost Conijn has inspired the character of the protagonist of Tommy Wieringa’s novel: Joe Speedboat, edited by De Bezige Bij [The Busy Bee], 2005. Which has won countless awards. Although Joost Conijn distances himself from the matter saying that anyone who knows me knows that there are notable differences with Joe Speedboat.

Denis Ponté (1964, Geneva)

A photographer who combines his work in the studio with his teaching activity at the University and his travels around the world, capturing what his eyes see in a very direct way. Says Serge Desarnaulds (actor of Jean Luc Goddard and writer): “A photographer whose commitment is manifest in many of his works (Left for Dead, 1994; Au bord du monde, 1995; Histoire de vivre, 1998; Face à elle, 2015). That commitment, artistic and social at the same time, marks a recognizable independence of spirit and ethics, together with the responsibility of their work, as well as the freedom to create without fitting into a limiting economic framework and outside of any institutional affiliation that could reduce your demands. That attitude has its price and is worthy of admiration. These various aspects make him an artist whose talent has been highlighted, especially when his images have as their theme the portrait or the natural and social environment observed during a trip. […] Few words are needed to designate this talent: a gift that knows how to capture the emergence at the right moment, that is to say, at that unexpected moment that we always wait for and that we will continue to wait for a long time since the fleetingness of the impression appears and reappears.

Throughout his career, Denis Ponté has developed numerous artistic projects with a social theme. Some of his most representative works are: Laissé pour mort (Geneva, 1995), Face à Elle (Geneva, 2015); I understand. Do you? (Cairo, 2016), Portraites parlés (Martigny, Valais, Switzerland, 2019), Facing them, La Posta Foundation (Valencia, 2019), Homo Artifex, Bancaja Foundation, Sagunto, 2021 (includes video-interviews). In addition to photography, he shares his experience in workshops held in West African countries.

Toni Serra / Abu Ali (Manresa, 1960 – Barcelona, 2019)

Preach and bear fruit

Although in recent decades it is frowned upon to approach the work of an artist from his biography, due to the tendency to extol a supposed genius spirit, the truth is that in the case of Toni Serra / Abu Ali it comes in handy to understand his work. In their career, as in their lives, they have coexisted with a critical attitude, which includes relevant texts such as “Open the vision”, with audiovisual works that have sought to create another imaginary, different from the one that constantly invades us through the media, including the cinema, some audiovisual works steeped in spirituality, even religiosity, remarkable. In that context, we could say that he did not just preach, but he also bore fruit.

Toni Serra passed away suddenly in 2019 in Barcelona, after a life from here to there, both in a physical and mental sense. In fact he adopted a middle name ―Abu Ali― is quite significant in this regard. Abu Ali means “son of Ali” in Arabic. As explained by Imam Alejandro Alí Badrán, who writes in the newspaper La Voz, from Córdoba, Argentina: “The genealogy of names”, 11.13.2012; the Arabs rarely use their own name and refer to each one as “the son of…” or “the father of…”, or “the mother of…”, consequence of the importance given to genealogy, a transcript in turn of the importance given to the family group and the clan. In this context, we have not been able to find out (yet) who Ali must have been, if it was a real person, adopting his name as a pseudonym. Although it will not hurt to remember that Ali is a fairly common family name, particularly in Morocco. Toni Serra lived a lot in Morocco. In this sense, when reference is made to his biography, it is usually said that he lived between Barcelona and Marrakesh (in some source we have been able to read that in a village near Marrakesh, Duar Msuar, but we have not been able to locate it on the map). Before he lived in New York, between the end of the eighties and the beginning of the nineties, but as part of his training as a video artist. Although also in the United States he combined his side of political criticism with his search for new imaginaries (in this sense, his work “El canto de la abubilla”, published in 2015, is paradigmatic, although with images recorded in evangelical churches during his stay in New York at early 1990s). That being in one place or another, both in a physical and mental sense, can be appreciated even in his early formative phase, when as a young man he studied Art History, which are literary studies, but after graduating he went to New York to learn video art. A whole life “between worlds”. That is why the choice of “Al Barzaj” [“between world”] (13’, 2018) is particularly appropriate, in particular for “The Nomadic Life”.

Ulrike von Gültlingen (Bielefeld, 1966; lives and works in Berlin)

She has developed her artistic career in the field of photography, drawing and stage design. In 2004 she founded the Freiraum School of Arts in Berlin, of which she is the director. Within Freirarum [outdoor space] she created Freirarum-kinder e.V., a non-profit association, with the aim of giving children free access to art and culture and promoting their creative thinking and potential.

About the series of photographs “Hohrodberg”, made in Alsace, the artist has commented: “I love wandering, discovering places that are more than themselves, the apparently random things that follow a secret principle of human legacies, telling us stories or asking us riddles”. Because, effectively, the places portrayed hide a secret.

This method of work practiced by Ulrike von Gültlingen makes her akin to the artists of the Spurensicherung Kunst, an artistic movement little known outside Germany, despite occupying a specific section in Art of the 20th century, Taschen, 1998.

Enrique Gil Bazan (Zaragoza)

He is a geologist and paleontologist (he was part of the Atapuerca team ―linked to the Museum of Natural Sciences in Madrid―, which under the direction of Emiliano Aguirre received the Prince of Asturias Award in 1997), and also a novel writer (Homo Project. Atapuerca: under the threat of the international plot, Certeza Libros, Zaragoza, 2007; a novel of intrigue, action and suspense), and writes scientific popularization in different media, such as CatalunyaVanguardista – Digital Independent. He uses photography to illustrate his scientific work with images, as drawing was previously used for that purpose. His photographs of the sea of stones of Arroyo Cerezo, in Rincón de Ademuz, show us a landscape of undiscovered beauty, to which his work makes a notable contribution.

“The Nomadic Life and the place of Rincón of Ademuz”. Colloquium

![Toni Serra / Abu Ali: “Al Barzaj” [“Entremundos”], 13’, 2010.](http://fundacionlaposta.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/barzaj_diptic_recortado2.2-568x469.jpg)