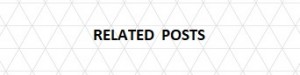

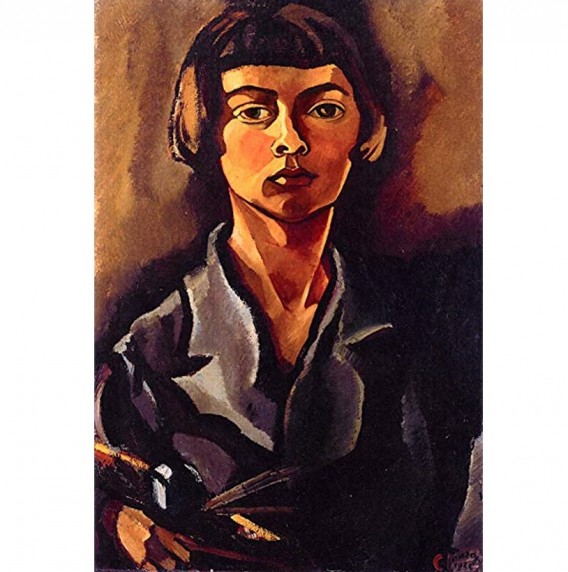

With the name Reinventing the representation: Dutch interwar art, 28 works from the Kunstmuseum Den Haag, the Netherlands, are exhibited in the IVAM Valencia, in addition to some more belonging to the IVAM collections, also from that historical period (George Grosz, Max Beckmann and Otto Dix). An exhibition that has been presented as a new Study Case, of which the museum has been developing since the new management took charge of it, in order to deepen the knowledge of pieces that are part of the collection, contextualizing them, through specific research and analysis work (however, this time there has been no publication). In this regard, it should be noted that, of the 28 works coming from The Hague, 11 of them are by Charley Toorop. Therefore, the need to focus attention on the works of this artist is growing. In addition, among the works of Charley Toorop that have come from the Kunstmuseum Den Haag is his series of self-portraits, which covers from his youth until his maturity, one of the most characteristic works of his career.

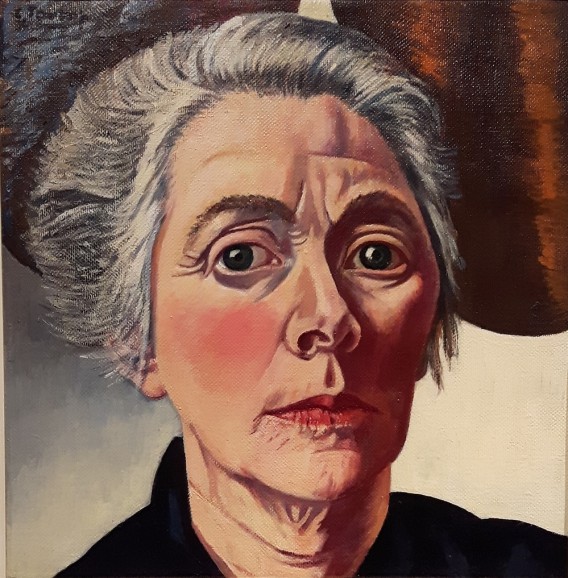

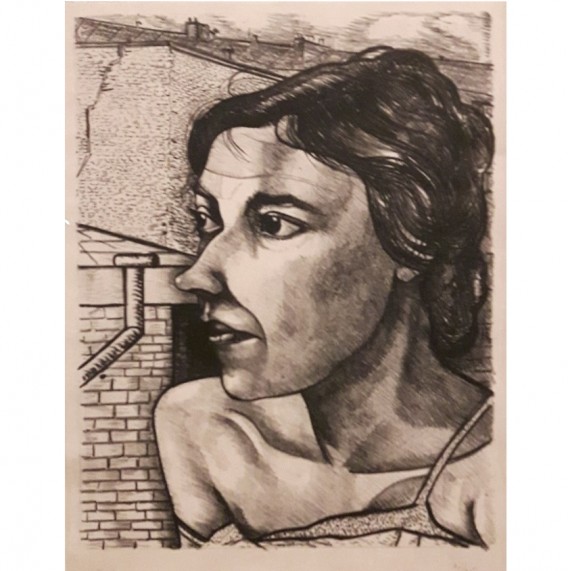

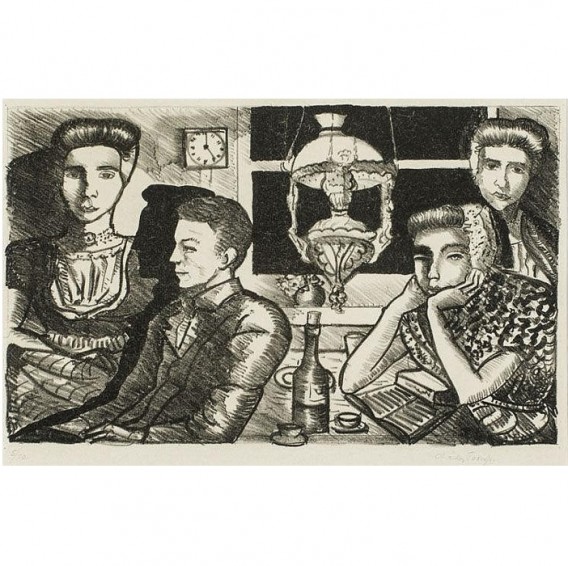

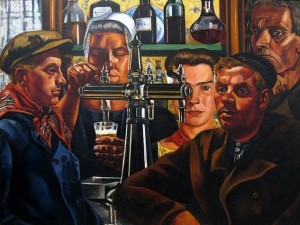

Aan de toog [At the bar], 1933.

Aan de toog [At the bar], 1933.

Self-portraits aside, Charley Toorop’s work was characterized by his paintings of laborers and farm workers, whom she represents like tanned men and endowed with enormous dignity. In spite of the attempts on the part of the critic to frame it in the German New Objectivity, which was being produced by those same dates, the truth is that she was unmarked whenever she had occasion, while expressing her preferences for Georges Braque. This inclination can be seen in one of the works exhibited now in the IVAM: “Two paraffin jugs with newspaper” (1942). It is a still life in which the typical food, ceramic bowls and vases for pouring wine, typical of the Dutch tradition of still life, have been replaced by workers’ tools and a newspaper of the time, a medium associated with the struggle worker in some circles (it must be borne in mind that for many years, those that correspond to her stay in Bergen ―where she would be one of the engines of what has been called the Bergen School― her companion was the historian anarchist Arthur Müller-Lehning, who would create the avant-garde film magazine i10, organ of the Film League, in which Joris Ivens participated among others).

Charley Toorop laughed a little at the New Objectivity artists, saying they were “interesting”. She wanted to identify with Braque, but the truth is that the work of Charley Toorop is related to that of Jan Toorop (his father), and not only because of a matter of blood ties, but above all because of a deep communion between them. That is why it is often cited as one of the fundamental works of the Toorop “Three generations” (1941), in which it appears with her father (a sculpture by John Radecker, which can be seen in Roterdam at the Museum Boijmans), she same self-portrait (another self-portrait) and also one of her sons (Edgar Fernhout), who would follow in his footsteps as an painter, all three forming a triangle exhibiting a strong family bond (very typical of Indonesians). Jan Toorop was born in Purworejo, on the island of Java, which at that time was part of the Dutch East Indies (in 1858). He studied European art, which was then taught as universal art, first in Batavia (Jakarta) and then in Holland (Delft and Amsterdam), as the colony did well (in fact, his father was a colonial post officer, married to a western). He developed his career as an artist in Holland, Brussels and London, encompassing a very wide plurality of styles, but in which he stood out the most, which is ultimately his most own style, it was what is usually called its symbolist era, an antecedent of Art Nouveau. These motley images (an example of horror vacui), full of wavy and curved plant shapes, are a direct influence of traditional Java art. It is paradoxical that something that is considered as European as Art Nouveau, Jugendstil in Holland and Germany, Modernism in Spain, etc., may have its origin in Indonesia. But even more paradoxically, when Jan Toorop returned to the Dutch East Indies, then as a renowned artist, hired by large Dutch companies to make the ceramic murals so characteristic associated with that art form, those works have gone down in history as colonial art. Although lately in Indonesia there is a review of whether Modern Architecture, and Art Nouveau so closely associated with that type of architecture, all this is really as alien to Indonesian tradition as it has been interpreted at first; an interpretation, on the other hand, typically western, that qualifies as Indonesian only what fits the concept coined in Holland, and by extension in the west, called “Mooi Indie” (“Beautiful Indonesia”), a genre of painting that developed in the Dutch East Indies in the 19th century, characterized by representing natural beauties (landscapes, beautiful women dressed in traditional ceremonial dresses, suffered peasants in the rice fields …), which was announced at the Universal Exhibitions that were celebrated at that time, with the aim of intensifying the tourist attraction of “Our most precious jewel”. From the perspective of “Beautiful Indonesia” it would be that, modern developments such as that carried out by Jan Toorop, despite their roots in Indonesian art, would be excluded, not responding to the petrifying colonial vision of artistic tradition in a series of issues considered as indigenous. But many in Indonesia are already showing their disagreement with this state of affairs. See about it here.

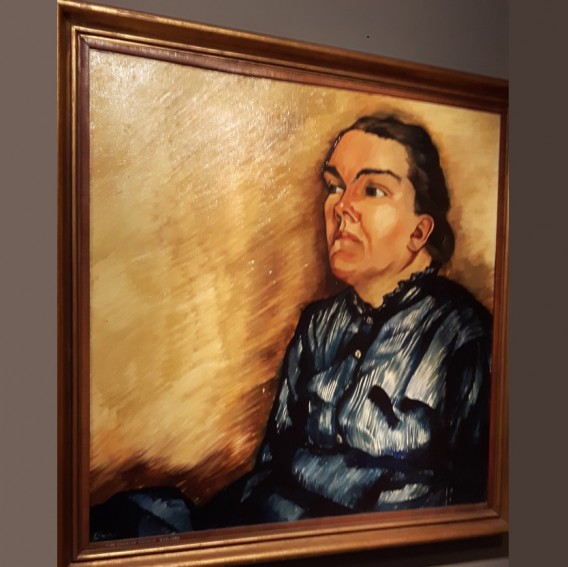

Drie generaties [Three generations], 1941.

Drie generaties [Three generations], 1941.

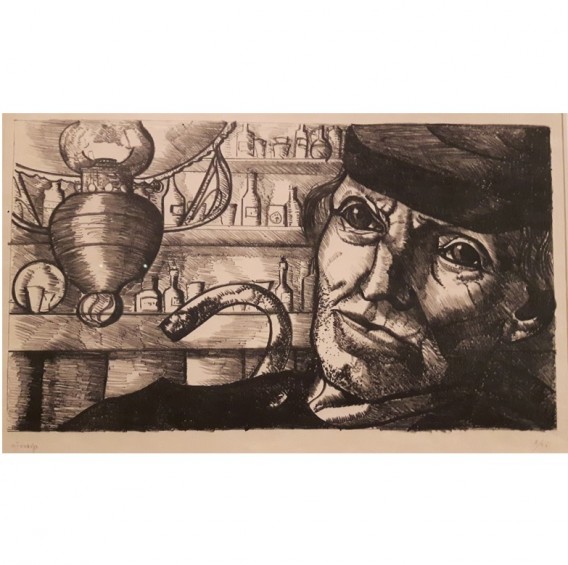

Within the plurality of styles that characterizes Jan Toorop’s work, leaving aside the set of works that would constitute what would later be known as Art Nouveau, the line of work that exerted a major influence on Charley Toorop was that of social realism. His work “Proletarian Suffering” (1901-1902) is attached, which is a good example of what is being said.

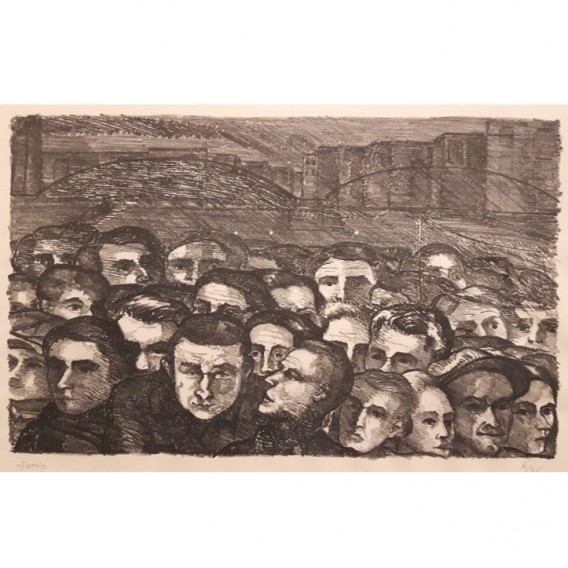

Jan Toorop, Gelof en loon [Proletarian suffering], 1901-1902.

Jan Toorop, Gelof en loon [Proletarian suffering], 1901-1902.

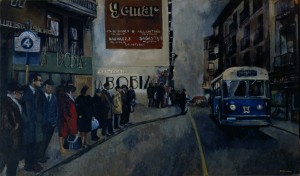

As for the contextualization of the work of Charley Toorop in the Valencian collections ―which there is, but not so much in the works of the New Objectivity belonging to the IVAM collections―, better to refer to the collections that houses in the Museum of Fine Arts of Valencia, and within them we must make a special mention to some works of Genaro Lahuerta, in particular his Works before the Civil War [The Museum of Fine Arts of Valencia is cited as the main depositary of Genero Lahuerta’s works in Valencia, although the one shown does not know where it is deposited].

Genaro Lahuerta, Seafaring procession (1930)

Genaro Lahuerta, Seafaring procession (1930)

It is known that the division of the collections between the IVAM and the Museum of Fine Arts is not peaceful. The case of the attachment of the Ignacio Pinazo collection to the IVAM funds is the most striking, but it is not the only one. And not so much because this ascription, although conditioned by the will of the family of the painter who made the donation, lacks justification, but because it is an isolated case, in a museological context in which the collections of the end of the century XIX and principles of the XX have been traditionally assigned to the Museum of Fine Arts (at the beginning of the 21st century there was an attempt to create a 19th century Museum that did not prosper). Consequently, when we refer to the period 1870-1939 (the imperial phase of the development of capitalism at that time; in the Spanish case of less intensity, although not for less prominence), we have to think fundamentally about the collections of the Museum of Fine arts. And in that context, the most appropriate reference that connects Valencian artistic activity that is not academic and that can be equated with non-avant-garde European currents, is ―very prominently― the works done by Genaro Lahuerta at that time.

Although, whom we have had in mind all the time while writing this article is Amalia Avia. But that is another story.